Ever since radios became common automotive accessories, music and motor vehicles have played a role in each other’s existence. The first production car radios were sold during the 1920s and FM radio came to US-built vehicles in 1952.

These were followed by the automotive record player, tape players and William Lear’s 8-Track cartridge system. Over the years, millions of unravelled cassettes would be hurled from car windows before that technology was replaced by the CD stacker, MP3 interface and Spotify.

The sounds coming from these devices have changed radically but through it all has run a genre known as ‘The Driving Song’. These may focus on particular vehicle models or reflect the cultural aspects of cars and driving but what they have in common is an urgency in the beat and, as with Golden Earring’s 1973 Radar Love, a need to quickly reach the driver’s destination.

The USA with its established automotive culture, long stretches of interstate highway and deserted rural roads was a natural habitat of The Driving Song.

Early examples were obscure, and most have disappeared into the depths of history. One that still is played regularly and inspired similar tunes though was Jackie Brenston’s ‘Rocket 88’. Released in 1951, this upbeat blues song co-written by Brenston and Ike Turner paid homage to Oldsmobile’s rapid Rocket 88 and rates as one of the first rock ‘n roll hits.

Another African American rocker to draw heavily on US car culture for his material was Chuck Berry. Maybelline, No Money Down and You Can’t Catch Me were among the songs that sent a message to millions of younger listeners across the world that a car was their ticket to independence and romantic success.

However, Berry’s battle with a romance-stifling seat belt in No Particular Place To Go may have set back acceptance of these life-saving devices by several years.

Participation in the surf culture invariably involved access to a motor vehicle and literally hundreds of surf/car/drag strip tunes were penned and recorded during the 1960s.

People not involved with hot rodding or the sport of drag-racing would have no clue as to what a ‘dual quad’, ‘4:11 gears’ or ‘rail job’ might be, but kids who were ‘hip’ to car-oriented terms would nod approvingly as they cruised their daggy old Dodge to the drive-in cinema or burger bar.

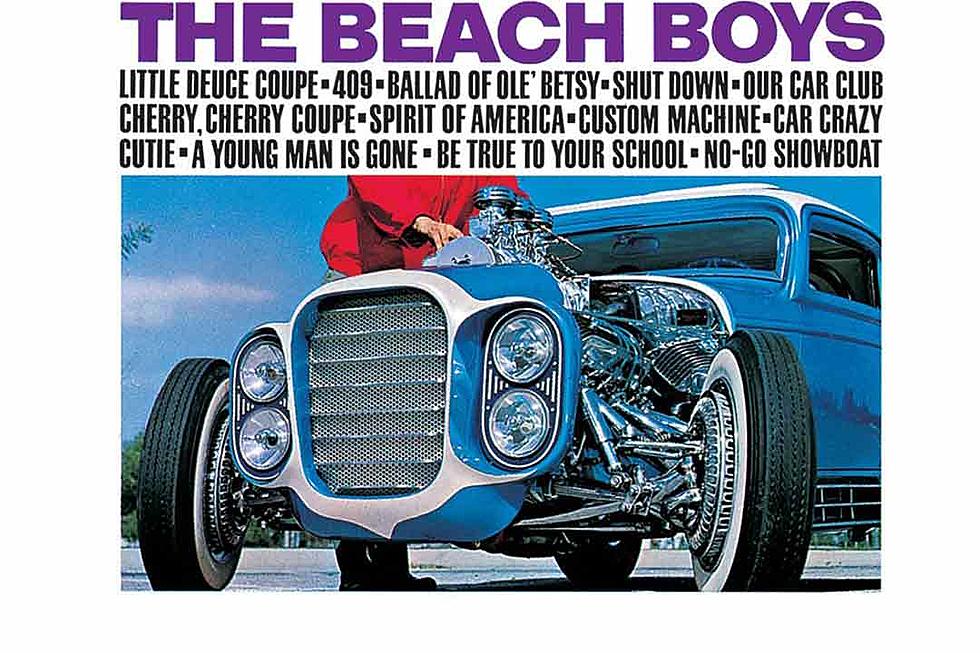

California’s Beach Boys were the kings of musical car culture with whole albums of car-oriented tunes and huge hits like My 409, Surf City and Fun, Fun, Fun (till daddy took the T-Bird away).

America also loved a good teen tragedy song and cars provided the backdrop to tales of big crashes and lost loves. Early in the peace came the anguish of Paul Petersen’s Tell Laura I Love Her and Teen Angel from Mark Dinning but the definitive work has to be Jan and Dean’s Deadman’s Curve.

It told the story of a race between a then new Jaguar E Type and Chevrolet Stingray along a treacherous section of Hollywood’s Sunset Boulevard. Released in 1964 it prophetically appeared two years before Jan Torrence’s near-fatal crash on the same road in his own Corvette Stingray.

By 1975 the culture of drag racing and muscle cars was fading but nobody told Bruce Springsteen. His Born To Run album included two of the most evocative car songs ever recorded – Jungleland and the title tune; with characters like the Magic Rat in his ‘Hemi-powered drone’ participants in an apocalyptic culture where cars are the only means of escape.

Hot on the heels of Bruce and the Rat came the age of Disco and it did very little to thrill the jeans and jacket brigade. In place of hard-driving rock however appeared banjos, finger pickers and Good Ole Boys in black Trans Ams or orange Chargers with the doors welded shut.

Jerry Reed in his Smokey and The Bandit persona was ‘Eastbound and Down’ with a Trans Am clearing the way. Up in the hills some country boys with a high-flying Dodge were being deified by Waylon Jennings in his theme tune to the Dukes Of Hazzard TV series, then over in Detroit Johnny Cash spent years pinching parts from a Cadillac factory to build his own in One Piece At A Time. Move back to the Deep South and Steve Earle was losing his daddy, a load of moonshine and a big-block Dodge to Copperhead Road.

British bands with the exception of The Beatles Baby You Can Drive My Car left automotive references pretty much alone and it would take pioneering New Wave performer Tom Robinson to build some car cred with his big-selling ‘2-4-6-8 Motorway’ and the lesser known ‘Grey Cortina’.

Australia listened and related to releases from overseas, but it took considerable time before cars would become an element of down-under music culture.

The ice broke with a clatter and bang in 1975 when Bob Hudson’s epic Newcastle Song went to Number 1 on the music charts and along the way paid homage to the humble FJ Holden. Not quite matching Hudson’s talent for lyrical humour but equally infectious was Ted Mulry’s Jump In My Car.

Obscure but historically accurate was the Auto Drifters Birth Of The Ute which during the late-1970 celebrated Ford Australia’s invention of the Coupe Utility. The song would later be covered by Daddy Cool.

Music released during the recent past stood little chance of commercial success unless accompanied by a memorable video. Cars, especially cars made decades before the youthful consumers of such music were born, have for a long time been viewed as vital to this very specific branch of filmmaking.

Cars as music video props can be used many contexts, providing the director and production designer remain aware that they have been hired to sell recorded music and not make a car commercial. Whoever in 1991 ran some stunning visuals behind Marc Cohn’s Silver Thunderbird did a great job of the latter; heightening demand for open-top T-Birds while the song remained a minor hit.

Few of the videos that feature cars can be bothered at all with current models. The models they highlight are invariably ‘classics’ and frequently from the era of the US-made ‘muscle car’. Some it must be said aren’t quite as their designers intended; leaping and lunging on ‘low-rider’ air suspensions or pimped to the max in classic Gangsta style.

They can also incorporate aspects of popular culture, as in The Gorillaz track Stylo which mimics the car chase/road trip movies made famous during the 1970s by projects like Smokey and The Bandit and The Blues Brothers.